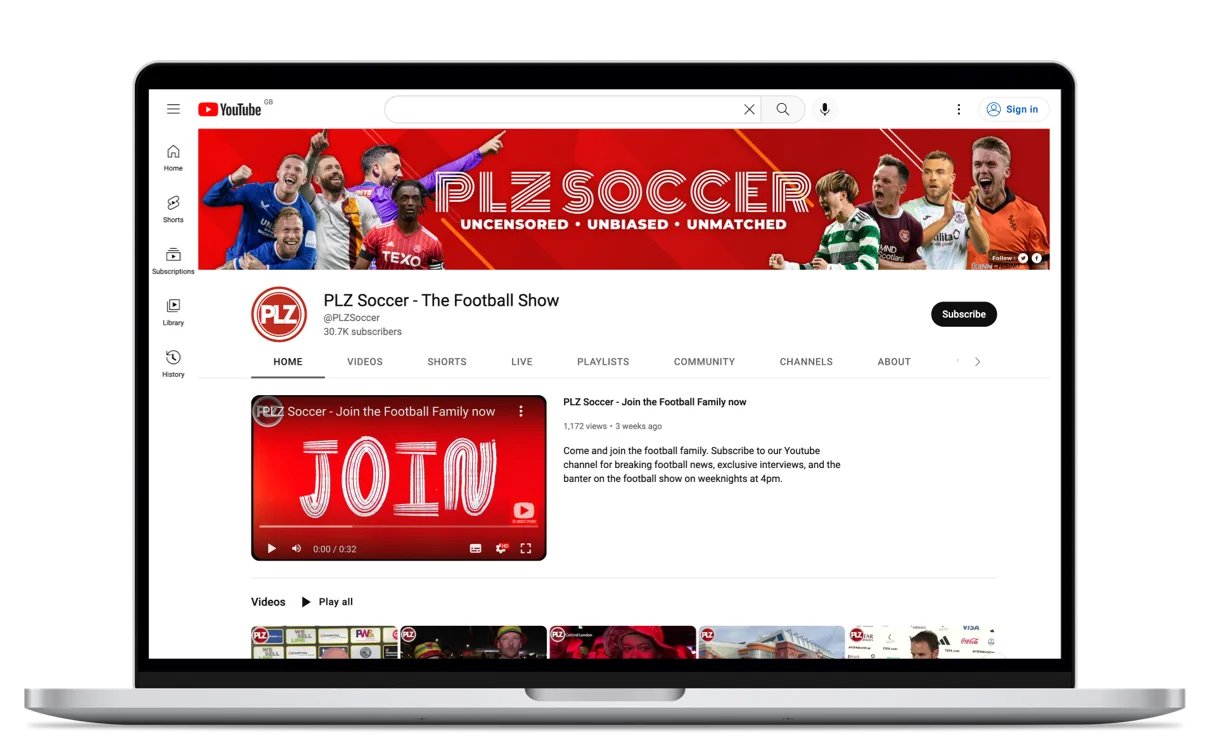

PLZ Soccer –

The Football Show

Unbiased. Uncensored. Unmatched.

Subscribe now for the latest Scottish and international football news, opinions and breaking stories from pundits who don’t hold back.

If you’re looking out for the most up to date football news, including scores, fixtures and transfer rumours, head to the Football Show on PLZ Soccer. We cover football fixtures and scores in the English Premier League, the Scottish Premiership, and other divisions from world football.

With a razor-sharp analysis of every game from our roster of pundits and updates on all of the movers and shakers during each transfer window, we can keep you in the know. The world of football moves quickly, and PLZ Soccer has got our ears to the ground.

Whether you want to keep up to date with managerial hiring and firing or new footballing prospects rising their way through the ranks, we have the interviews, insight, and latest football bulletins you need. Read our articles or watch our videos to stay in the loop or buy football merchandise from our online shop.

Proudly Sponsored by